Quick Start

React డాక్యుమెంటేషన్కు స్వాగతం! ఈ పేజీ మీరు రోజూ ఉపయోగించే 80% React కాన్సెప్ట్లకు పరిచయాన్ని అందిస్తుంది.

You will learn

- కంపోనెంట్లను ఎలా క్రియేట్ చెయ్యాలి మరియు వాటిని ఎలా నెస్ట్ చెయ్యాలి

- మార్కప్ మరియు స్టైలును ఎలా జోడిన్చాలి

- డేటాను ఎలా ప్రదర్శించాలి

- కన్డిషన్లను మరియు లిస్ట్లను ఎలా రెండర్ చెయ్యాలి

- ఈవెంట్లకు ప్రతిస్పందించడం మరియు స్క్రీన్ను ఎలా అప్డేట్ చెయ్యాలి

- కమ్పోనెన్ట్స్ మధ్య డేటాను ఎలా పన్చాలి

Creating and nesting components

React apps are made out of components. A component is a piece of the UI (user interface) that has its own logic and appearance. A component can be as small as a button, or as large as an entire page.

React components are JavaScript functions that return markup:

function MyButton() {

return (

<button>I'm a button</button>

);

}Now that you’ve declared MyButton, you can nest it into another component:

export default function MyApp() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Welcome to my app</h1>

<MyButton />

</div>

);

}Notice that <MyButton /> starts with a capital letter. That’s how you know it’s a React component. React component names must always start with a capital letter, while HTML tags must be lowercase.

Have a look at the result:

function MyButton() { return ( <button> I'm a button </button> ); } export default function MyApp() { return ( <div> <h1>Welcome to my app</h1> <MyButton /> </div> ); }

The export default keywords specify the main component in the file. If you’re not familiar with some piece of JavaScript syntax, MDN and javascript.info have great references.

Writing markup with JSX

The markup syntax you’ve seen above is called JSX. It is optional, but most React projects use JSX for its convenience. All of the tools we recommend for local development support JSX out of the box.

JSX is stricter than HTML. You have to close tags like <br />. Your component also can’t return multiple JSX tags. You have to wrap them into a shared parent, like a <div>...</div> or an empty <>...</> wrapper:

function AboutPage() {

return (

<>

<h1>About</h1>

<p>Hello there.<br />How do you do?</p>

</>

);

}If you have a lot of HTML to port to JSX, you can use an online converter.

Adding styles

In React, you specify a CSS class with className. It works the same way as the HTML class attribute:

<img className="avatar" />Then you write the CSS rules for it in a separate CSS file:

/* In your CSS */

.avatar {

border-radius: 50%;

}React does not prescribe how you add CSS files. In the simplest case, you’ll add a <link> tag to your HTML. If you use a build tool or a framework, consult its documentation to learn how to add a CSS file to your project.

Displaying data

JSX lets you put markup into JavaScript. Curly braces let you “escape back” into JavaScript so that you can embed some variable from your code and display it to the user. For example, this will display user.name:

return (

<h1>

{user.name}

</h1>

);You can also “escape into JavaScript” from JSX attributes, but you have to use curly braces instead of quotes. For example, className="avatar" passes the "avatar" string as the CSS class, but src={user.imageUrl} reads the JavaScript user.imageUrl variable value, and then passes that value as the src attribute:

return (

<img

className="avatar"

src={user.imageUrl}

/>

);You can put more complex expressions inside the JSX curly braces too, for example, string concatenation:

const user = { name: 'Hedy Lamarr', imageUrl: 'https://i.imgur.com/yXOvdOSs.jpg', imageSize: 90, }; export default function Profile() { return ( <> <h1>{user.name}</h1> <img className="avatar" src={user.imageUrl} alt={'Photo of ' + user.name} style={{ width: user.imageSize, height: user.imageSize }} /> </> ); }

In the above example, style={{}} is not a special syntax, but a regular {} object inside the style={ } JSX curly braces. You can use the style attribute when your styles depend on JavaScript variables.

Conditional rendering

In React, there is no special syntax for writing conditions. Instead, you’ll use the same techniques as you use when writing regular JavaScript code. For example, you can use an if statement to conditionally include JSX:

let content;

if (isLoggedIn) {

content = <AdminPanel />;

} else {

content = <LoginForm />;

}

return (

<div>

{content}

</div>

);If you prefer more compact code, you can use the conditional ? operator. Unlike if, it works inside JSX:

<div>

{isLoggedIn ? (

<AdminPanel />

) : (

<LoginForm />

)}

</div>When you don’t need the else branch, you can also use a shorter logical && syntax:

<div>

{isLoggedIn && <AdminPanel />}

</div>All of these approaches also work for conditionally specifying attributes. If you’re unfamiliar with some of this JavaScript syntax, you can start by always using if...else.

Rendering lists

You will rely on JavaScript features like for loop and the array map() function to render lists of components.

For example, let’s say you have an array of products:

const products = [

{ title: 'Cabbage', id: 1 },

{ title: 'Garlic', id: 2 },

{ title: 'Apple', id: 3 },

];Inside your component, use the map() function to transform an array of products into an array of <li> items:

const listItems = products.map(product =>

<li key={product.id}>

{product.title}

</li>

);

return (

<ul>{listItems}</ul>

);Notice how <li> has a key attribute. For each item in a list, you should pass a string or a number that uniquely identifies that item among its siblings. Usually, a key should be coming from your data, such as a database ID. React uses your keys to know what happened if you later insert, delete, or reorder the items.

const products = [ { title: 'Cabbage', isFruit: false, id: 1 }, { title: 'Garlic', isFruit: false, id: 2 }, { title: 'Apple', isFruit: true, id: 3 }, ]; export default function ShoppingList() { const listItems = products.map(product => <li key={product.id} style={{ color: product.isFruit ? 'magenta' : 'darkgreen' }} > {product.title} </li> ); return ( <ul>{listItems}</ul> ); }

Responding to events

You can respond to events by declaring event handler functions inside your components:

function MyButton() {

function handleClick() {

alert('You clicked me!');

}

return (

<button onClick={handleClick}>

Click me

</button>

);

}Notice how onClick={handleClick} has no parentheses at the end! Do not call the event handler function: you only need to pass it down. React will call your event handler when the user clicks the button.

Updating the screen

Often, you’ll want your component to “remember” some information and display it. For example, maybe you want to count the number of times a button is clicked. To do this, add state to your component.

First, import useState from React:

import { useState } from 'react';Now you can declare a state variable inside your component:

function MyButton() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

// ...You’ll get two things from useState: the current state (count), and the function that lets you update it (setCount). You can give them any names, but the convention is to write [something, setSomething].

The first time the button is displayed, count will be 0 because you passed 0 to useState(). When you want to change state, call setCount() and pass the new value to it. Clicking this button will increment the counter:

function MyButton() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

function handleClick() {

setCount(count + 1);

}

return (

<button onClick={handleClick}>

Clicked {count} times

</button>

);

}React will call your component function again. This time, count will be 1. Then it will be 2. And so on.

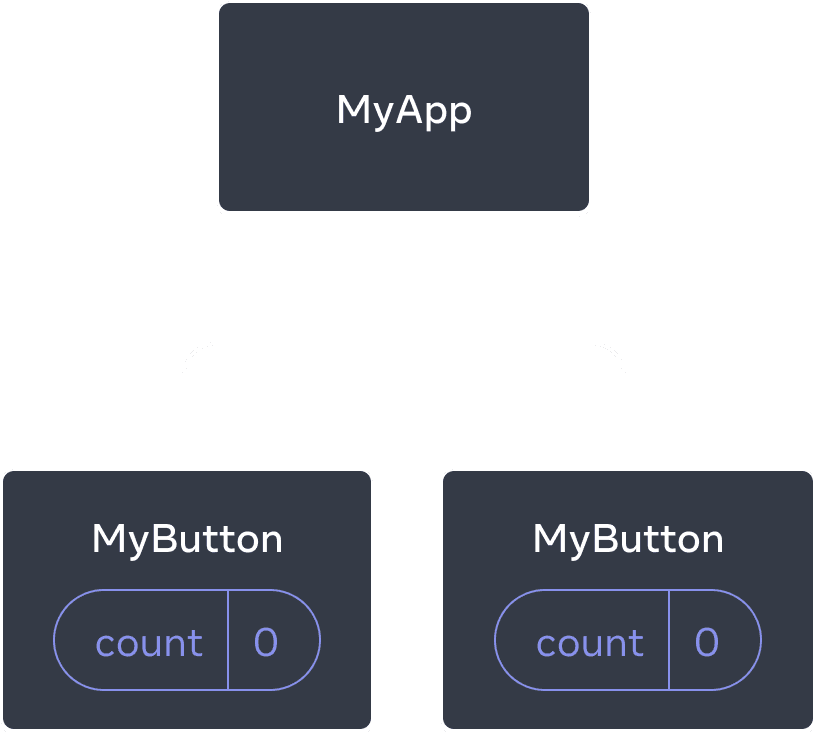

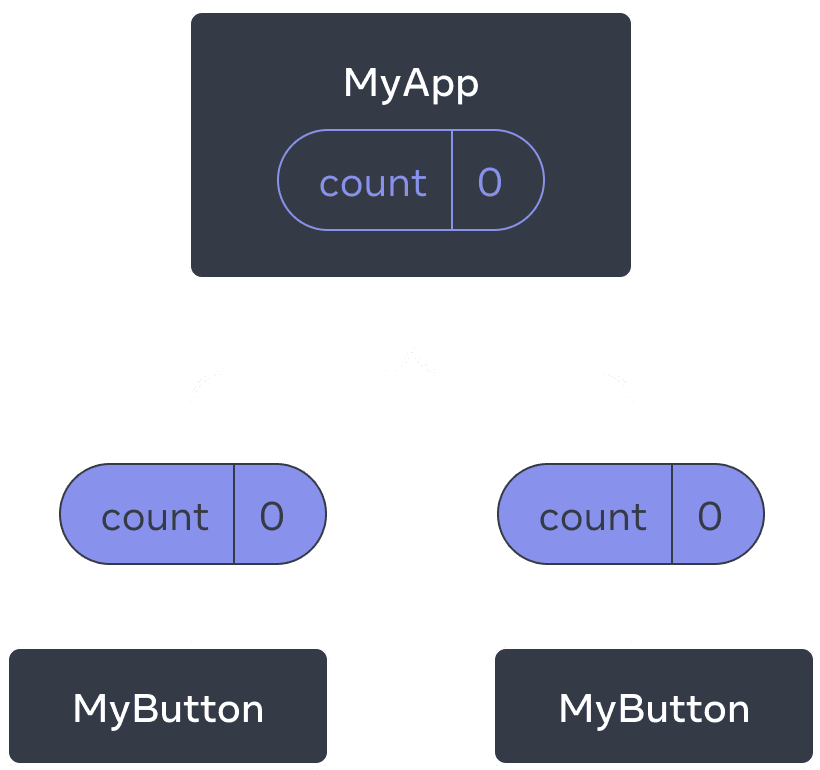

If you render the same component multiple times, each will get its own state. Click each button separately:

import { useState } from 'react'; export default function MyApp() { return ( <div> <h1>Counters that update separately</h1> <MyButton /> <MyButton /> </div> ); } function MyButton() { const [count, setCount] = useState(0); function handleClick() { setCount(count + 1); } return ( <button onClick={handleClick}> Clicked {count} times </button> ); }

Notice how each button “remembers” its own count state and doesn’t affect other buttons.

Using Hooks

Functions starting with use are called Hooks. useState is a built-in Hook provided by React. You can find other built-in Hooks in the API reference. You can also write your own Hooks by combining the existing ones.

Hooks are more restrictive than other functions. You can only call Hooks at the top of your components (or other Hooks). If you want to use useState in a condition or a loop, extract a new component and put it there.

Sharing data between components

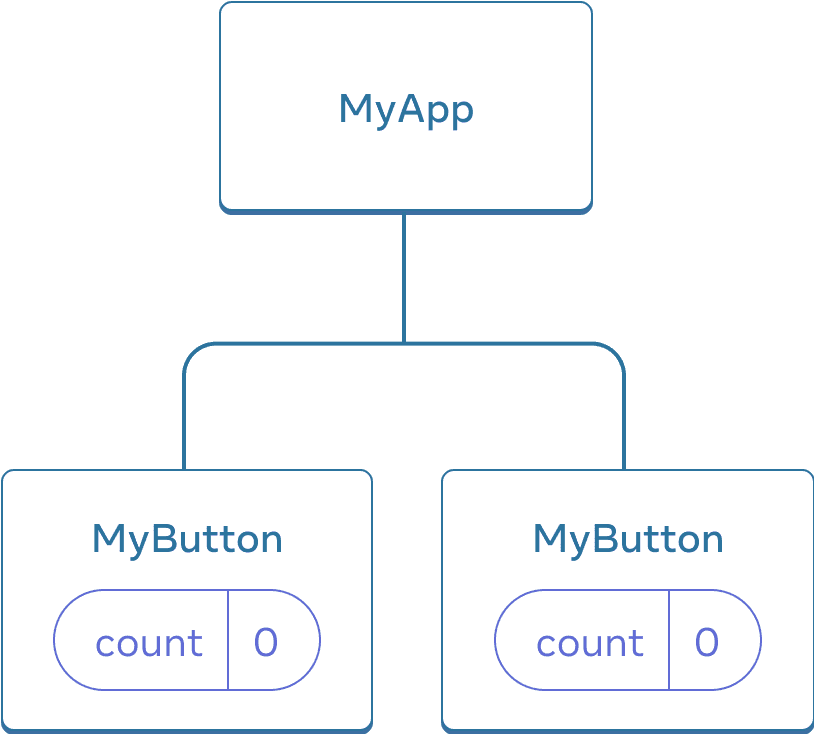

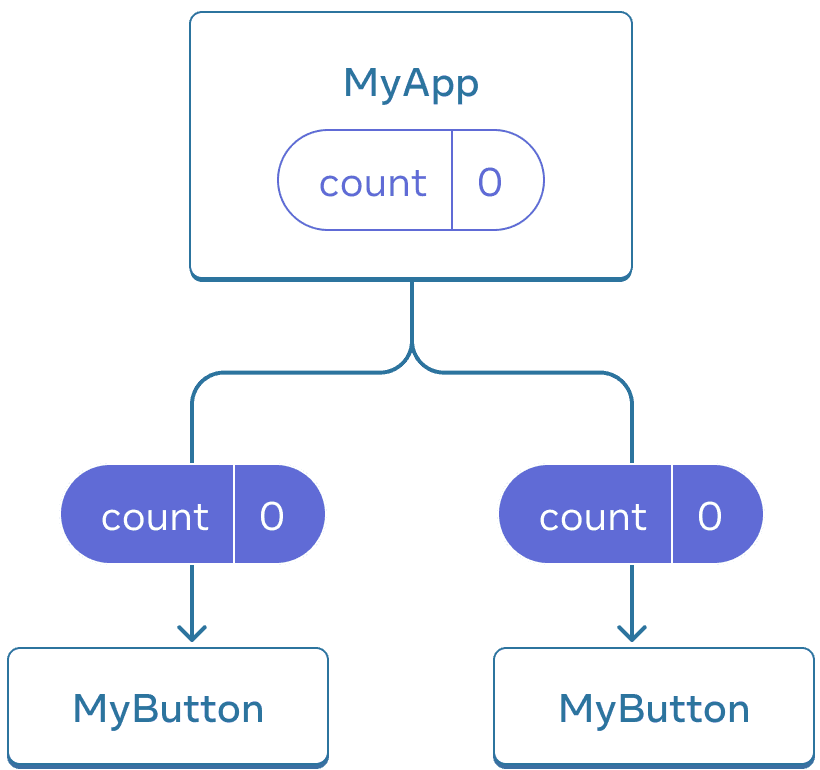

In the previous example, each MyButton had its own independent count, and when each button was clicked, only the count for the button clicked changed:

Initially, each MyButton’s count state is 0

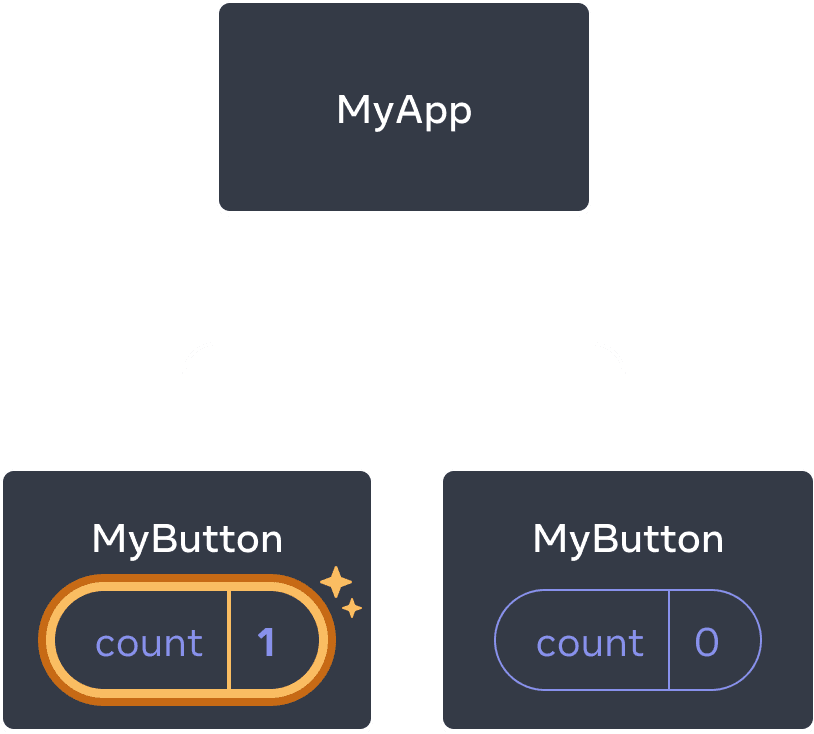

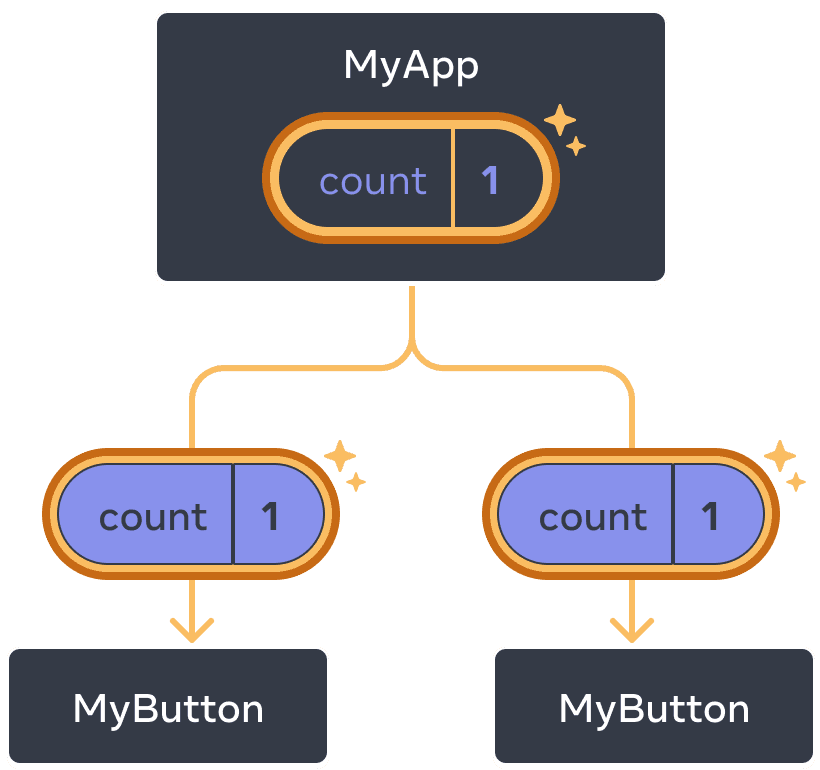

The first MyButton updates its count to 1

However, often you’ll need components to share data and always update together.

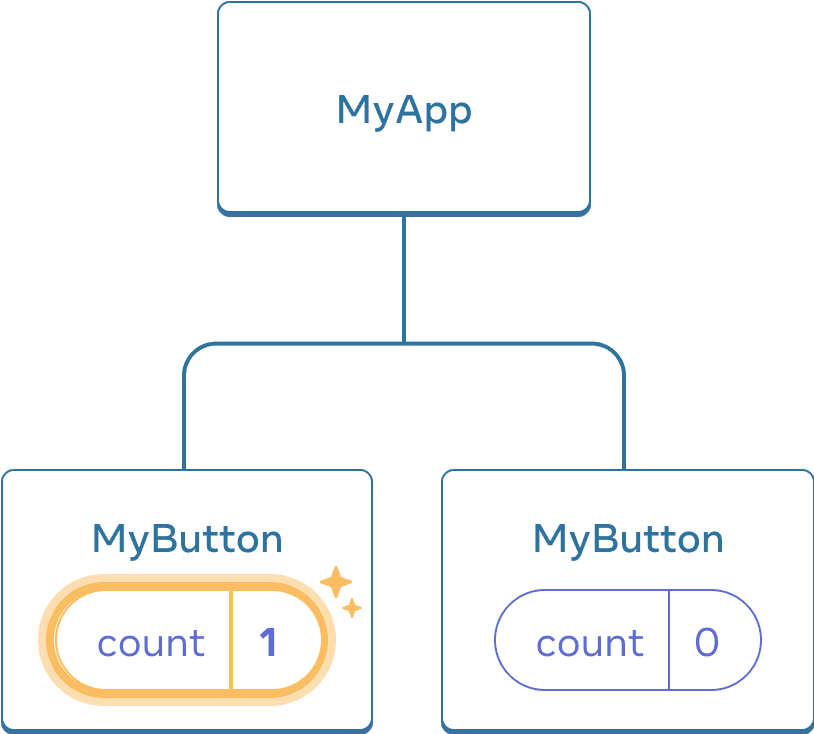

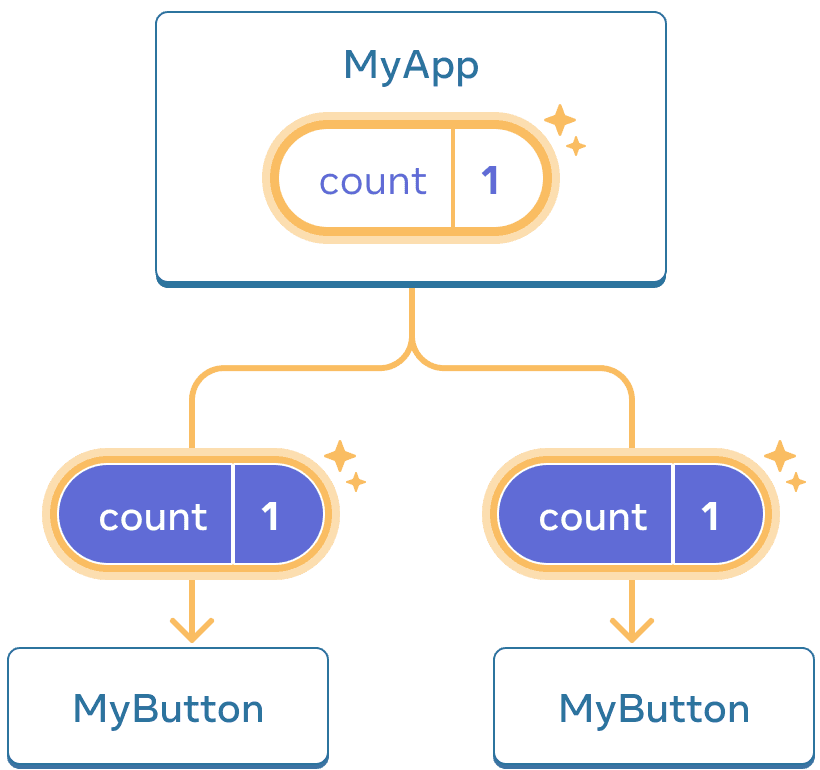

To make both MyButton components display the same count and update together, you need to move the state from the individual buttons “upwards” to the closest component containing all of them.

In this example, it is MyApp:

Initially, MyApp’s count state is 0 and is passed down to both children

On click, MyApp updates its count state to 1 and passes it down to both children

Now when you click either button, the count in MyApp will change, which will change both of the counts in MyButton. Here’s how you can express this in code.

First, move the state up from MyButton into MyApp:

export default function MyApp() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

function handleClick() {

setCount(count + 1);

}

return (

<div>

<h1>Counters that update separately</h1>

<MyButton />

<MyButton />

</div>

);

}

function MyButton() {

// ... we're moving code from here ...

}Then, pass the state down from MyApp to each MyButton, together with the shared click handler. You can pass information to MyButton using the JSX curly braces, just like you previously did with built-in tags like <img>:

export default function MyApp() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

function handleClick() {

setCount(count + 1);

}

return (

<div>

<h1>Counters that update together</h1>

<MyButton count={count} onClick={handleClick} />

<MyButton count={count} onClick={handleClick} />

</div>

);

}The information you pass down like this is called props. Now the MyApp component contains the count state and the handleClick event handler, and passes both of them down as props to each of the buttons.

Finally, change MyButton to read the props you have passed from its parent component:

function MyButton({ count, onClick }) {

return (

<button onClick={onClick}>

Clicked {count} times

</button>

);

}When you click the button, the onClick handler fires. Each button’s onClick prop was set to the handleClick function inside MyApp, so the code inside of it runs. That code calls setCount(count + 1), incrementing the count state variable. The new count value is passed as a prop to each button, so they all show the new value. This is called “lifting state up”. By moving state up, you’ve shared it between components.

import { useState } from 'react'; export default function MyApp() { const [count, setCount] = useState(0); function handleClick() { setCount(count + 1); } return ( <div> <h1>Counters that update together</h1> <MyButton count={count} onClick={handleClick} /> <MyButton count={count} onClick={handleClick} /> </div> ); } function MyButton({ count, onClick }) { return ( <button onClick={onClick}> Clicked {count} times </button> ); }

Next Steps

By now, you know the basics of how to write React code!

Check out the Tutorial to put them into practice and build your first mini-app with React.